From the RECORD Archives: ‘An Architecture of Democracy: Three Recent Examples from the Work of Louis H. Sullivan’

‘An Architecture of Democracy: Three Recent Examples from the Work of Louis H. Sullivan’

By A.N. Rebori

Architectural Record, May 1916

So much has already been said and written about the general character of Louis H. Sullivan’s practice that any additional remarks on this subject, in order to be of real value, must be derived from a fresh point of view, or else suffer the ignominy of repetition. I will chance monotony, however, by repeating what I believe to be the greatest tribute ever paid a living architect by a critic. The late Montgomery Schuyler has said “a new work by Sullivan is the most interesting event which can happen in the American architectural world today,” which was indeed a compliment, the utterance of which anyone should feel justly proud to have inspired. If there is an occasional dissension from this opinion, it is because the work of this master is not fully understood or its meaning and intent not entirely grasped. I use the word “master” in its fullest sense, for surely there is no denying that none but a master-mind could conceive and execute such a work as his, and yet I have heard it said on many occasions that “Sullivan excels in details,” and that “his architecture is not so interesting,” and further, that “without this fancy detail there would be nothing to it at all,” which remarks tend to show a gross ignorance of the fundamental principles that underlie all of Sullivan’s architecture.

If we agree that the ornamentation of his buildings is beautiful, we are bound to admit from even the most casual study that it is beautiful, not only as ornament, but by reason of the part it plays in the general scheme of development. It is, to say the least, the true handwriting of the designer expressing itself in his own particular flourish or grace. The great lesson that Sullivan’s work teaches is not one of detail or ornament, but one more comprehensive in which the solution of a particular problem is given artistic and practical expression. It is in his analyses of the conditions at hand and in the straight-forward and brilliant manner by which conditions are made to function that the works of this master architect fairly stand out in all their bigness. It is the expression from within outward, or as Sullivan himself so aptly puts it, “mind over matter.”

Take for example, any one of his bank buildings, and we are bound to admit that the solution of the problem was the result of a previous knowledge of the conditions involved, combined with inventive imagination and technical and artistic skill of a most unusual order. For the lack of a better word we might term all this “creative genius.” Call it what we will, it is architecture.

That there is a formula to which Sullivan adheres in the development of his work is quite apparent; but of one thing we can rest assured, it is not one of duplication, for, with no two problems alike, no two buildings are given the same expression. It is an architecture of pure intent, with form following function as its basic principle. To understand function requires an intimate knowledge of practical requirements; to express form demands artistic skill combined with an intimate knowledge of structural material. Hence Sullivan arrives at a solution of a given problem by means of a carefully worked-out plan in which the allotted areas arranged as to needs dominate the treatment, and the outward appearance of the building is permitted to develop accordingly, with the method of construction taking form naturally. But, as all structural conditions are not pleasing to the eye or worthy to be classed as architecture, his artistic instinct causes him to add decoration or adjust propositions, as the case may be, obtaining a justness and balance that is both structural and beautiful.

© Architectural Record, May 1916

In contrast with this method of work, we have the buildings of the many architects throughout the land, who, by their faithful reproductions of monuments of the world, not only have been successful professionally, but have achieved a high pinnacle of fame in their own field. Sullivan, at least, stands in a class by himself, for indeed his architecture is not one of imitation, but an architecture that gives a truthful and idealistic modern interpretation of a given problem in a most intimate and individualistic way. It is the true spirit of democracy, expressed in terms of building, significant of our times, our people, and our life. I believe it to be all this, and more, by virtue of the skill displayed by the designer in the artistic spacing of his decoration, in the placing and scale of the detail, and in the study given the design as a whole based on function, logic and art. The problem confronting him in any case is to make the most of the advantages and minimize the disadvantages, and to do so with the least possible sacrifice of the strictly utilitarian purpose of the structure itself, and yet to make as expressive, harmonious and beautiful a building as conditions permit.

In the light of these remarks, it might interest the reader to hear how Sullivan solves a given problem. Of course, there must first be a problem, or rather a client desiring a new building, which is an event usually scarce at the present time. But in this particular case, the architect was informed by a banker who had seen one of Mr. Sullivan’s bank buildings that it was the intention of the committee on building to erect a new bank to house their institution. Being broad-minded and up-to-date businessmen, strongly in favor of a rational architecture, they invited Sullivan to study their requirements and prepare drawings. Complying with their call he left for the scene of expectations, Grinnell, Iowa, in the central part of the State, personally to interview his prospective clients and look over the original site. After meeting the committee, he set about the customary task of learning the needs of the proposed building, not in the casual way, but in the most detailed manner possible. Judging by the sketches and notes which were made with the aid of an ordinary desk rule on sheets of common yellow paper acquired at a nearby apothecary shop, not a single part of the machinery that was to make up this bank’s organization was overlooked. Here we find not only the allotted space to the various departments, but the different desks, cages, and all minor details worked out to an exact scale. For three whole days he talked and drew, rubbing out as changes were made, fitting and adjusting to the satisfaction of all. The dimensions are clearly marked on these original drawings in plan, section and elevation, leaving no doubt as to the exact layout of the building. I asked Mr. Sullivan how it happened that his preliminary sketches were worked out in such a definite manner, and he answered quite simply that “those were the requirements as given, and it only remained to jot them down on paper,” which he did, using the sheets of yellow paper available at the time.

© Architectural Record, May 1916

These notes or preliminary sketches are the most exquisite bits of architectural memoranda that it has ever been my pleasure to see. In their making, every possible element that was to play a part in the future project was fully analyzed and put into architectural form in plan, section and elevation, and what was more, this was all done in a little office adjoining the bank president’s room in the old building at Grinnell, Iowa, in full view of and with aid of the building committee. Before leaving the place, the owner knew from these sketches exactly what his building was going to look like, from the arrangement of the smallest detail to its largest mass, all of which received his approval.

The development of the sketches into working drawings proceeded in close accordance with the original scheme, for, having once determined the exact conditions and requirements, there was no further need for change, for the vital organ, the plan, which plays the important role, was determined upon and accepted. Hence, we see how Sullivan arrives in a most intimate manner to a logical expression of the functionating duties of the building itself. All this is done without the aid of that exquisite ornamentation for which there is no formula, but which is the personality of the artist himself, or, as I have previously put it, his handwriting.

Consequently, by the abandonment of every architectural convention that does not conform in strict loyalty to the problem involved, the simple force of need becomes a principle of beauty. That is why no two buildings from the hand of Sullivan are alike, no more than two persons possess the same physiognomy. Each problem has its own particular solution, derived solely on its merit, and worked out on an intelligence of the highest order, the result of which can bear analysis, and still prove that “form follows function.” It is the organic simplicity of this unified work of Sullivan’s that will live long after his ornament has ceased to play so important a part in the minds of its observers.

© Architectural Record, May 1916

I am convinced his work possesses style, but that style is a distinctly personal one, emanating from the source, and that source is Sullivan. The remarkable part of it remains in the fact it is original, and does not bear copying, for to be able to do likewise, or rather to possess the ability to do likewise, would be to do something else, equally as good and just as personal to the individual. Surely it is not given to many of us to be original, and we can all realize that nothing can be more depressing than the undertaking to do something new by an architect who is unaware of what has already been done or who has not learned how to do it. Originality as we often find it is usually a “stunt,” or a peculiar twisting, or a disarrangement of accepted form, whereas Sullivan’s original designs signify a natural growth, the steady advancement of which abounds with knowledge and judgement. Chance does not play a part in the solution of a problem controlled by such a mind, and yet it is the imaginative quality so rarely possessed, but in Sullivan’s case, so paramount, that makes his buildings great.

The bank building at Newark, Ohio, is quite as different from any other bank building that has preceded it, as it is different from the bank building at Grinnell, Iowa. The fact that one is not like the other clearly shows the designer’s intention to treat each problem on its needs, regardless of stereotyped precent. In the design for the Grinnell building a single-story structure is required and frankly expressed, whereas in the case of the building at Newark a two-story structure is demanded and likewise takes proper form. The choice of materials—varying from an entire terra cotta treatment for the facades on the one hand, and a brick and terra cotta treatment on the other—and their variated handling show the versatility of the architect. The same remarks apply to all three buildings herein illustrated, the largest covering a plot of ground forty-three by seventy-five, and the smallest a small corner lot twenty by sixty. None of these buildings compares in magnitude with Sullivan’s greatest bank at Owatonna, Minn., yet they are all strikingly successful, each in its own characteristic way.

© Architectural Record, May 1916

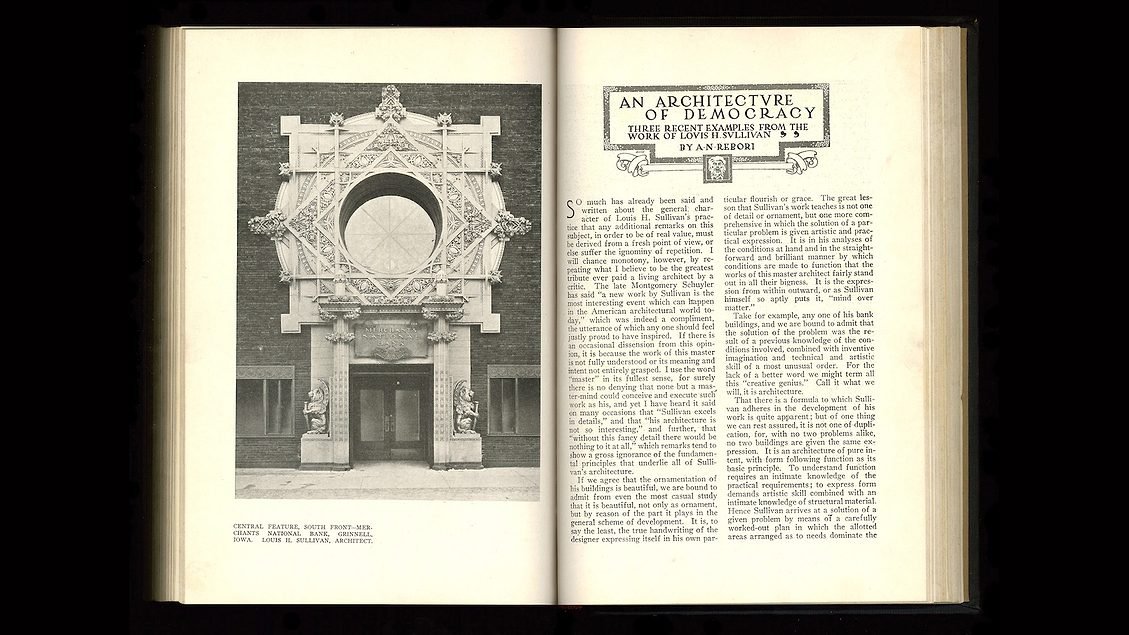

The Merchants National Bank at Grinnell, Iowa, presents a brilliant, dignified exterior, with its entrance motif of delicately modeled lace-like design clearly cut and imbedded against a background of rich toned brickwork as the dominant feature of its design. The side is simplicity itself in the form of a flat wall treatment with a single principal window of leaded glass preceded by a closely spaced colonnade possessing exquisitely ornamented spreading capitals within the face of the enclosing brick frame. Besides the principal features of the facade are to be found the windows to the directors’ and women’s room discreetly and frankly placed in a manner evidently not intended to play an important part in the general composition. The crowning feature consists of a rich ornamented terra cotta coping slightly silhouetted against the sky. The exterior brickwork is of wire-cut shale brick of mixed shades, ranging in color from blue-black to golden-red and laid with raked joints. The crown effect is of brown terra cotta with gold inlaid, and the griffins or lions on the flank of the entrance are of fire gilt terra-cotta. Over the door, marked in lettering which is in keeping with the character of the ornament, is a statuary bronze sign or nameplate.

The slender metal columns with spreading caps supported on a solid brick wall high above the sidewalk, on the east front, are covered with gold leaf which sparkles in the sun, adding unusual charm and brightness to the exterior. Separated from the leaded glass by a three-inch air space, hermetically sealed, is a thickness of polished plate glass, on the outside face. The effect is that of a dream-like futuristic picture, mysterious but superb in color. At the corner, protruding like a sore thumb, is the “old clock,” a relic of the bank’s former home.

© Architectural Record, May 1916

If the exterior frankly proclaims the plan, it is to the interior that we must turn to see the plan in working order. And yet here again the same consistency in design is found followed out in every department. The direct and simple treatment of the front, depending largely on its color scheme for interest, truthfully corresponds to the interior forms or plan. The same thoughtful consideration is everywhere apparent. From the moment the visitor enters past the vestibuled doors the workings of the bank are thrown open to view, disclosing at first sight the intricate mechanism of the open doors to the steel-lined vaults on the central axis. Then comes to view on the right and left the glass, brick and bronze partition screens that divide the space around the central public lobby. It is like the open works of a watch as seen through its crystal back cover.

At the street corner of the plan is conveniently placed the combination directors’ and consultation room within easy access for the public, and with a wide opening provided with a concealed side coiling wood shutter adjoining the officers’ quarters. This shutter is used only during directors’ meetings. A brick and marble counter separates in a most informal manner the office space from the public. The tellers’ and bookkeepers’ space, with their dividing cages of straightforward material, completes the arrangement of the right side of the plan, while on the left, fully equipped with up-to-date features, are placed a women’s room, savings department and men’s room in the order named. Between these two divisions is placed a vault at the rear of the building, two stories in height, with an elevator serving the main floor level and the basement providing the only ingress for the lower level of the vault.

© Architectural Record, May 1916

The interior fittings are housed in a single lofty room, limited only in size by the outside walls and roof of the building. In general, the interior decoration is confined to a carefully studied series of units composed of the material employed, and paneled off in a decisive manner from the simple skylighted glass and wood paneled ceiling to the side walls of plaster, marble and brickwork. The principal flood of natural light is admitted through the large opalescent east window, so admirably marked on the outside of the building, and is augmented by the central skylight, which throws a soft, diffused blanket of light that covers every portion of the room and gives a strong decorative treatment to the otherwise simple ceiling. The circular port window over the entrance adds a note of brilliantly harmonious colors by its leaded glass design that lends to the effectiveness of the otherwise flat high wall, of which it is the radiating note. Contrasted with this brilliant symphony of color, which is decidedly meant to be the high pitch of this dignified and orderly interior, is the rest of the glass work, which takes on a mottled soft colored flat tone of vibrating transparency. A recall of the high-key color work in an unusual but successful manner is found in the treatment of the interior clock, which is set in a glass mosaic field flatly imbedded in the brickwork over the vestibule feature.

Bright accents of color are added in the way of leaded glass inserts to the delicately carved oak framed electroliers desk lamps, and the leaded glass panels of the large east window. These spots add color value to the entire scheme and help liven up the flat faced walls. Comparatively dark finished quartered oak frames enclose large plaster ceiling panels painted a light shade. The floor is of gray-pink Tennessee marble in oblong shapes and laid with hair joint. The assorted, thin, Roman shape brick for inside brickwork are carried to a height of 13 feet around the walls and are capped above the vault doors by a richly designed and executed topping or crown of fire gilt terra cotta. In elegant contrast with the direct brick treatment are the counter tops of Vermont verde-antique marble in flat slabs of almost three inches thick. They project slightly at the statuary bronze wickets where the projecting marble deal plate is of a grand antique marble a shade richer in color. The woodwork throughout is of quartered oak, stained to a hickory shade, with the grain in every case effectively permitted to add to the decorativeness of the interior. Mouldings are tabooed in the handling of all woodwork.

© Architectural Record, May 1916

Wherever wood carving is indulged in, it adds a distinct charm, because it is well done, and it gives a greater appreciation of the wood. Some of this carving appears on the upright parts of the check desk, and again at the spandrels above the doors. It is decidedly of a wood character and sets off and enhances the beauty of an otherwise flat and direct wood treatment. Wherever the various materials are used there is no sham on the part of the designer, nor is there any doubt on the part of the observer as to what the various materials represent. Wood is made to look like wood, and likewise all the other materials are honestly given expression. What is more remarkable is that these simple expressions are given an interpretation that is at once intelligent and beautiful. Surely, we find no instance where the problem is shirked or covered up by an incumbent disguise of something that it is not. Here without doubt is seen the hand of a master craftsman with something to say, and that something presented in a most plausible manner. The result is not the same old story over, and over again, but an architectural treatment that is as pliable to the mind of Sullivan as the conditions leading up to the solution of a problem permit.

© Architectural Record, May 1916

Thus we see in the little bank building for the Home Building Association Company at Newark, Ohio, another solution and expression of an architectural work that is as different both in general composition and detail from the Grinnell Bank, which I have just described, as the requirements of the latter problem differed from the requirements of the first. In the latter we find a condition which frankly required a one-story treatment, whereas in the Newark building it is just as obvious from the treatment of its design that the structure is of two stories. And yet what a temptation it would be to almost any other architect to string a row of classic columns under a generous cornice across the facade of both these buildings! But this article has not to do with class architecture, nor is it my intention to compare Sullivan’s works with those of other architects. I merely digress at this point to bring home this vital force and fundamental truths of the architecture now under consideration.

To return to the subject of building in Newark, it is plain that both the first and second-story plans are the natural outcome of a carefully studied set of requirements to be taken care of on a corner plot of ground of small dimensions. In this case a two-story building was essential, hence its designer takes advantage of the imposed requirements by placing the various offices of the business organization on the second story, occupying the ground floor with tellers’ and officers’ quarters, within the easiest possible access for the transient trade or public. The main entrance is on the short side of the lot, while the entrance to the upper story is purposely placed at the opposite end of the long side. The window openings throughout are placed and arranged with a daring adherence to the strictly utilitarian purpose of the structure itself that speaks highly of a competence that is born of understanding. These windows are spaced broad and low, as they should be, where light is essential and conditions permit.

© Architectural Record, May 1916

Once again, if the plan is as clearly expressed as it is intelligent, it is to the elevations that we must turn in order to grasp the simple force of this direct bit of planning, for here we see how by the skill of the architect, in his emphasis and his subordination in the artistic spacing of his decoration, in the placing and scale of his detail and study given to his design as a whole, based on function, reason and logic, the result is made highly artistic and effective. The designer once more made the most of the advantages presented by the plan, and correspondingly minimized the disadvantages, and yet here has accomplished this without the last sacrifice of the strictly utilitarian purpose of the structure.

Thus, the effect attained is an expressive, harmonious and beautiful building, based on fact artistically enforced. For example, Mr. Sullivan does not hesitate to subordinate the side entrance in its relation to the general facade. As a matter of fact, he frankly treats it to a consideration of secondary importance by flanking its right side only with the stem of the delicate burst of floral ornament, which blossoms above and which is repeated on the opposite of the large frame enclosing the side window openings of the two floors. I asked Mr. Sullivan why he placed these efflorescent spots as he did, and he answered simply that “it was done to take the eye away from the side opening so that the front entrance would dominate and clearly mark the public entrance to the building.”

© Architectural Record, May 1916

The exterior is treated in carefully arrayed panels of soft greenish gray terra-cotta, with ornamented sand-finished borders, leaded glass windows and inlaid glass mosaic, rich and mellow, of a soft mottled shade, with the front panel more strongly emphasized by its gold lettering in a field of green shaded glass. The contrast between the gray colored terra cotta and the exquisitely tinted glass mosaic work gives the exterior of this little building a richness and charm that is at once distinctive without being overdone. I will not attempt to analyze the character of the exterior ornamental detail, for that would really be attempting too much, especially when there is no other age, style or period with which it can be compared, as far as its relation to that particular style or period is concerned. It is distinctively of today, and is characteristically Sullivan, and all his name implies. Its very freedom breathes a joyous spirit of renaissance, of true democracy. Further than this, I do not care to go for fear of detracting from the vital importance of Sullivan’s work, which is, as previously stated at the beginning of this article, an architecture of organic significance, in which the force of need is the underlying principle from which it is evolved. The interior of “The Old Home,” as the Newark building is called, is as successfully handled in all its minutest details as the exterior. The general view gives a fair idea of the decorative scheme. Although the ghost-like reflections on the polished marble facing and plate glass screen tend to distort and make flimsy the solidity of the walls, this effect does not appear in reality. Color is extensively used throughout from the rare antique marble floor carried around the counter and side walls below to the rich polychromatic frieze of conventionalized design, and the richly paneled decorative ceiling above. For the teller’s screen a simple and effective arrangement of bronze grilles on plate glass supporting a continuous bronze light reflector is made to suffice. The woodwork is mahogany with doors of a single flat panel of carefully selected grain African mahogany veneer from Togas Island, off the west coast of Africa.

© Architectural Record, May 1916

Judging solely from the illustrations herein shown, one is apt to get the impression that the interior color scheme is rather loud. This is not the case, however, for in reality the decorative work is harmoniously blended, rich and effective, and well united and held in place. It is one fault is that it runs the risk of becoming unrestful because of its exuberance. Taking this building as a whole, both in its exterior and interior treatment, it is as successful as it is refreshing. In its scope, the design of this building shows a remarkable diversification and considering that the practical considerations are admirably taken care of and not slighted in the least, what the designer has accomplished aside from its artistic quality is very impressive. It argues not merely an unremitting application, but the establishment of a very clean cut and effective method of work determined by modern construction and uses of the place.

Herein lies the secret of the positiveness of all of Sullivan’s buildings. They can stand the most severe analysis from a structural and practical standpoint and yet reveal nothing commonplace about the manner in which the structure is given architectural significance.Every one of his buildings, I repeat, is the solution of a particular problem, and as such the result is as successful for its own purpose as it is inapplicable to any other. Add to this a most intimate knowledge and masterful handling of building material and decorative ornament of a most personal nature, and the result is a living architecture that defies classification. At least, it only can be classed under one heading, and that is the architecture of Louis H. Sullivan. It is an architecture that is all embracing, derived from the source, and leaving no question open as to its authorship. It is conscientiously applied to all problems large or small. In fact, no work is too small to receive or demand careful consideration and due study by his matured intellect.

© Architectural Record, May 1916

Witness for example, the studied simplicity of the Land and Loan building at Algona, Iowa. Here is a little structure clearly designed with a view of the part it was to play as a real estate office in a town of secondary importance. To describe it would be superfluous, as the complete details are fully set forth in drawings of this building shown.

In conclusion, it is to be hoped that the initiative elements brought out by Sullivan’s work will not cause these charming designs to be copied and reproduced elsewhere, but that modern architects already advancing so rapidly along new lines of departure will value the lesson these buildings advance without copying their exact form. If this is done, the great architectural talent in America now engaged in the attempt to expand along classic lines will, without doubt, eventually develop a purely rational American architecture—an architecture of democracy.

© Architectural Record, May 1916

Bannister Fletcher has fairly sized up the present state of architectural endeavor in the following statement: “it is certain that there is a great future for American architecture if only the architects will as much as possible express themselves in the language of their own times. No advance can be made by the copying of ancient buildings as has been done in certain cases constituting a retrogressive movement, and showing a sad want of appreciation of the true value of art. The great historic styles must of course be well studied, not for the forms with which they abound, but for the principles which they inculcate, much in the same way that the literature of the past is studied in order to acquire a good literary style. If architecture is thus studied a good result is assured and the architects will produce works reflecting the hopes, needs and aspirations of the life and character of the age in which they live.”

Finally, when the opportune moments arrive and Sullivan’s entire works are compiled and presented in book form, the feature that will demand attention will be the uniform character of his architecture. Then it will be possible to follow the long years of progressive growth that led up to the design of these three characteristic small buildings illustrated in this number. Very certainly, any perusal of his works reveal the facts that no attempt was made to liken the ancients to ourselves. On the contrary we will find that the designer was at some pains to impart into his style the mode and manner, the forms and colors of present times. In his architecture we have at least something that stirs and stimulates, something appeals strongly to the imagination and decidedly not an attempt to travesty the Greek or Roman, but an architecture replete with meaning and pregnant with a future that inspires us with a high and far-reaching hope.