THAI-PAKISTAN FRIENDSHIP MOSQUE

As this article is written from the perspective of a Thai Buddhist, the term ‘mosque’ evokes imagery of a dome-shaped, semicircular structure with intricate geometric designs. It also brings to mind smaller towers embellished with mosaic tiles, showcasing magnificent and detailed patterns. While it is true that not all mosques have a similar appearance, I seldom encounter structures that exhibit such a distinctively different design.

There is, however, a mosque in Bangkok that stands out from the norm for two primary reasons. Firstly, it is a five-story structure. Secondly, it deviates from typical mosque architecture by adopting a minimalist aesthetic and prioritizing the creation of high-quality functional spaces rather than intricate ornamental details.

One late afternoon, I had the opportunity to visit the Thai-Pakistan Friendship Mosque, located on Mahaseth Road in the Si Phraya subdistrict, one of Bangkok’s bustling commercial areas. Designed by Teechalit Architect, the building offers a unique interpretation of Islamic architecture, incorporating distinct forms and spaces while still preserving its religious identity and purpose.

While such characteristics may be more commonly found in places outside of Thailand, it was certainly surprising to see them here. And it wasn’t just a case of Islamic architecture. Compared to other religions, Thai-Buddhist temples rarely incorporate contemporary aesthetics into their designs. I’m not implying that it’s a negative thing, considering how universality, in the context of architecture, is frequently, if not always, linked to the West.

Before my conversation with the architect who designed this mosque, I took a moment to envision what the ‘House of God’ would look like in a world that is more diverse than ever before.

The sixty-year-old building created by and for the Pashtuns people of Bangkok

The origins of this mosque can be traced back 60 years, to a time when the number of mosques in Thailand was still quite limited. The Patan descendants, or Pashtuns, in Bangkok, along with their Muslim ancestors, joined forces to raise funds for the construction of a new mosque. This initiative aimed to provide the local Pashtun community with a suitable place for their daily prayers. The effort resulted in the establishment of the Thai-Pakistan Friendship Mosque, which remains the sole Pakistani mosque in Bangkok to this day.

The Thai-Pakistan Friendship Mosque was initially constructed as a single-story wooden building. After a span of twenty years, the first renovation took place. The extension was designed as a two-story structure, with half of it made of wood and the other half made of concrete. This combination was chosen to enhance its durability and provide ample space for accommodating a larger number of visitors.

By 2019, the building had begun to deteriorate significantly, reaching a state of devastation that rendered it beyond repair. The Pashtuns community in Bangkok made the decision to demolish the old building and replace it with a brand new mosque, and the architect, Teechalit Chularat of Teechalit Architect, has been selected to oversee the project.

A mosque on 400-square-meter land: Escaping the box

In general, the new mosque was built to be the simplest in terms of structure, spatial allocation, and orientation in order to make the best use of the 400-square-meter parcel of land on which it is built. The design was realized as a five-story box-shaped structure. The building’s axis (elevator shaft and stairs) is located in the back, with a properly divided interior functional program comprising the service area and parking space on the first floor, the multifunctional hall on the second floor, and the main prayer chamber on the third floor. The Thai-Pakistan Friendship Association’s headquarters occupies the fourth floor of the building, while the fifth and highest floor is just beneath the dome roof and houses a small hall of fame and museum space that welcomes outside visitors.

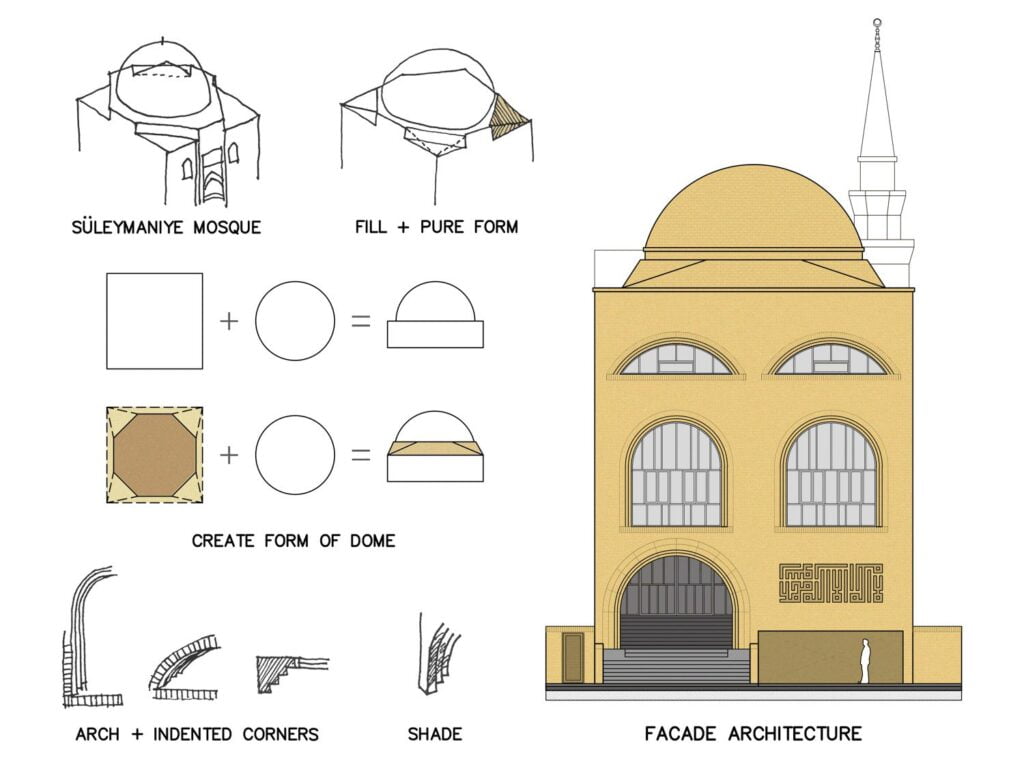

After the functional spaces were agreed upon, the architect’s next challenge was to figure out ‘how to make this box-shaped building less confined while still encapsulating the characteristics of Islamic architecture and Pakistani vernacular identity.’ Most importantly, the design must be able to accommodate Islamic religious activities and ceremonies (the structure was required to have one or more domes as a symbolic representation of the vault of heaven, all while taking into account the architect’s intention for the structure to incorporate minimalistic elements).

To resolve the confinement of the spaces inside a very thick, boxy building, the architect locates the openings and windows on every story to free the space up for sunlight and ventilation. The first-floor setback range is designed into an expansive stairway near the front of the building. The stairs not only accentuate the entrance area but also make the entire interior of the building appear larger due to the huge transition space that continues further into the interior functional spaces. Meanwhile, the inside-out perspective creates a picture frame, allowing users to observe their outside surroundings.

The vernacular identity of Pakistani architecture is represented by the orange bricks that are frequently used as the main component in the country’s historical Mughal architecture. The recess features of window and door frames, as well as the outside walls of the structure, render the dimension that minimizes the building’s substantial mass while enhancing the dynamic effects of light and shadow.

The most challenging element of the design is its practical use, which must be in conjunction with Islam’s sacred ‘directions’. The ‘Mihrab’ (a chamber in a mosque where the imam leads the prayer) of most mosques must face Qibla (the direction towards the Kaaba in the Sacred Mosque in Mecca, Saudi Arabia).

The challenges with the praying area were that, due to the deviation of the entire building layout within the given piece of land, a huge number of functional areas would have to be sacrificed. Other axes, such as the ‘Saf’ (Muslim prayer row), which uses the spaces on the second and third floors with wood and marble-patterned tiles, need to follow the sacred direction. The tiles are laid perpendicular to the Qibla, resulting in a somewhat deviated floor, even though the design still allows the space to be entirely functional for religious activities.