In Venice, an Architecture Biennale with a Dystopian Flair

I have seen the future. And it’s a headache.

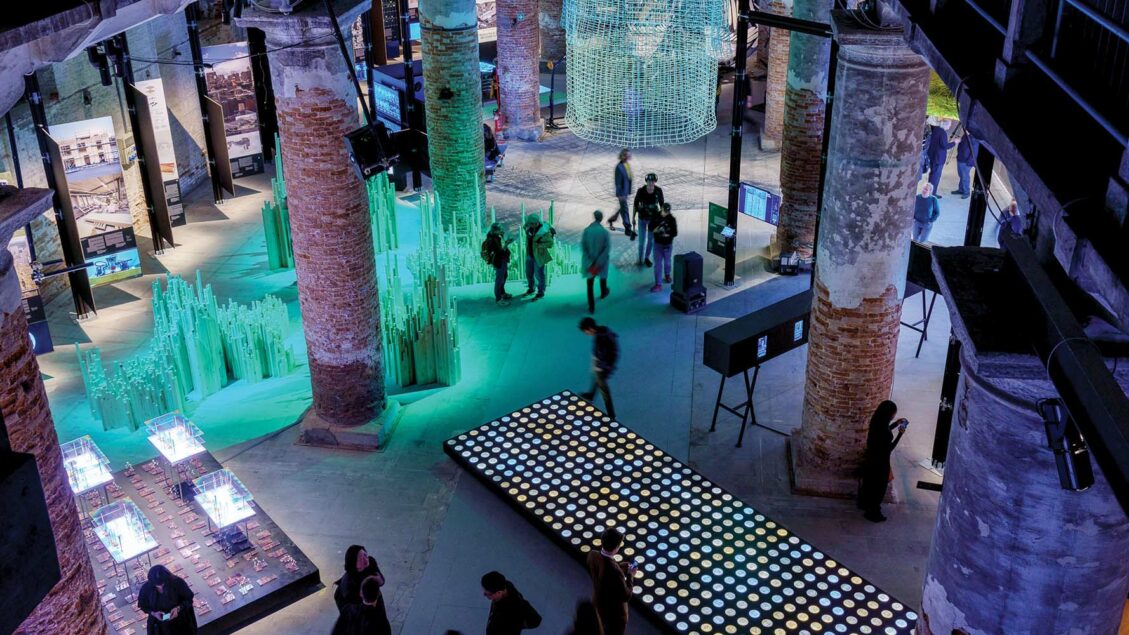

Carlo Ratti’s international exhibition at the 19th Venice Architecture Biennale is intended to be a searching, no-bad-ideas rap session on the human prospect—the possibilities, pitfalls, and space-faring AI-assisted freak-outs confronting global civilization in the 21st century. At least by the standards of recent biennials, the show’s premise is remarkably concise: riffing on (though not perhaps adequately crediting) the field of information theory, Ratti proffers 300 installations from some 750 contributors as sources of what he terms “intelligens,” vital practical clues for responding to pressing social and ecological crises. But the extraordinary density of the presentation fogs up any conceptual clarity his section might otherwise have possessed. Filled to the brim with drum-playing robots, oversize LED screens, and the occasional live Bhutanese wood-carver, the atmosphere in Venice’s chasmic Arsenale complex is that of a shadow-realm Coney Island, sans hot dogs and sans beach, where the only prize is the grim certainty that the end is nigh.

The densely-packed Arsenale features projections, hanging installations, and sculptural built works. Photo © Andrea Avezzù, courtesy La Biennale di Venezia, click to enlarge.

Studio Gang’s colorful contributions aid urban wildlife, including bats, birds, and bees. Photo © Tom Harris

This is not, to some extent, the fault of Ratti, still less of the individual exhibitors, many of whom turn up with outstanding work. For his part, the show’s MIT-based curator was kneecapped by the temporary closure of the Central Pavilion, the secondary facility that typically plays host to a substantial chunk of the Biennale. Had the space been available, it might have afforded a bit more breathing room for some of the Arsenale’s most intriguing material: Chicago’s Studio Gang brought a set of porcelain architectonic elements for aiding urban wildlife, among such bats, a favorite of principal Jeanne Gang for their “weirdly human” behavior; from the Sydney office of Grimshaw Architects, a project to turn data centers into “urban mixed-use opportunities,” in the words of the firm’s Erik Escalante; and, from New York urban-experimental studio Terreform One, a “DNA archive,” as founder Mitchell Joachim describes it, with living kelp acting as genetic hosts for architectural data. At times, the profusion of stuff—the succession of off-grid building prototypes (e.g., Deserta Ecofolie, from Chilean duo Pedro Ignacio Alonso and Pamela Prado) and speculative mobility systems (Norman Foster’s experimental water bikes, available for test drive at the Arsenale’s dock) and Rube Goldberg machines for turning Venetian canal water into coffee (from Diller Scofidio + Renfro, winner of this year’s Golden Lion, despite its not in fact being fully operational as yet)—almost achieves a kind of accidental sublimity. Such moments, however, are fleeting, the exhibition’s myriad parts inevitably getting in the way of the whole.

1

The Bahrain Pavilion (1) and Canal Café by DS+R (2) were both winners of a Golden Lion. Photos © Andrea Avezzù (1), Marco Zorzanello (2), courtesy La Biennale di Venezia

2

The national delegations are often excellent when taken individually, with or without Ratti’s framework in view. Among the strongest are a gaggle of teams from the Middle East: Qatar, the United Arab Emirates, Saudi Arabia, and Bahrain all came to town with revealing exposés of (respectively) regional housing types, agricultural strategies, historic preservation, and climate-change mitigation, the lattermost taking Golden Lion honors among the 66 countries that presented this year. In a Biennale so overstuffed and frenetic, some of the best ideas are the ones that slow things down and space things out—in the Danish Pavilion, for example, a display of dug-up odds and ends from the structure’s recent renovation, or the Serbian Pavilion, featuring large woven works suspended from the ceiling. A few steps away, Poland has come through with perhaps the subtlest, and definitely the snarkiest installation in the Giardini, Lares and Penates, which skewered the well-intentioned futility of signage, fire extinguishers, and other domestic minutiae that try and very often fail to help us. “It’s not so much architectural as anthropological,” says pavilion curator Aleksandra Kędziorek.

The Serbian Pavilion’s billowy installation is called Unravelling: New Spaces. Photo © Luca Capuano, courtesy La Biennale di Venezia

Good things can be found as well off-site, where assorted Venetian institutions new and old debuted design-themed fare. For the map-and-chart dork in us all, Fondazione Prada unveiled Diagrams: assembled by Rem Koolhaas’s AMO/OMA, upward of 300 archival and exhibition-copy documents provide an overview of schematic visual representation through the ages, from medieval religious tracts to late-1970s magazine infographics on inflation. (“Many of the original historical materials have to be regularly rotated,” noted OMA’s Giulio Margheri, “to ensure the paper is properly exposed and protected.”) A couple of vaporetto stops to the south, the newly launched Nicoletta Fiorucci Foundation staged its first-ever show—a site-specific work from artist-designer Tolia Astakhishvili, who lived in and among the detritus of the building’s deconstructed interior while making do and making objects from the mess. Curated by ubiquitous cultural dynamo Hans Ulrich Obrist, the show was a perfect fit for the structure, which was selected by its arts-patron leader for its relative flexibility. “The outside is listed [for protection],” said Fiorucci. “With the inside, we can do anything.”

3

Inside a 17th-century palazzo on the Grand Canal (3), the Fondazione Prada opened Diagrams: A Project by AMO/OMA (4). Photos © Marco Cappelletti

4

Other, less effective offerings could not be laid at Ratti’s feet. The basic ingredients of this year’s U.S. Pavilion sound promising enough: project studies from established practices like Weiss/Manfredi sit cheek by jowl with more research-focused work like Friends of Residential Treasures’s examination of Los Angeles porch culture. Under the direction of the Fay Jones School of Architecture and Design at the University of Arkansas, Porch, as the exhibition is called, does loving homage to the titular fixture of American residential architecture, and even features a shaded forecourt of its own—an impressive Marlon Blackwell–designed wooden armature projecting from the two wings of the U-shaped historic pavilion. Yet there’s a peculiar thematic cleavage between the literal porch that greets visitors on arrival, and the only metaphorically porch-y, welcoming-ish displays within, the sheer number of which nearly rivals the Arsenale for mass-per-volume. It is unfortunate, especially given the ingenuousness of the participants, many of whom were excited simply to be there. As one young Southern-born designer put it, during the pavilion party at the Peggy Guggenheim Foundation, “I never imagined I’d be in a place like this hearing the word ‘Arkansas’ so much.”

5

In contrast to the Baroque elegance of Diagrams, the U.S. Pavilion (5 – 7) had a down-home feel. Photos © Roland Halbe (5), Marco Zorzanello, courtesy La Biennale di Venezia (6 & 7)

6

7

Playing in the background of these assorted disappointments and confusions is a cultural and political climate of increasingly gloomy aspect. The Biennale as an institution faces an uncertain future: the director of next year’s art show, Cameroonian curator Koyo Kouoh, died suddenly during this year’s opening, at the age of 57; at the same time, the 2026 American Pavilion (and by extension any subsequent American Pavilion) is in jeopardy, as the State Department was late in soliciting proposals and has now attached bizarre ideological terms to the brief. The basic relevance of this Architecture Biennale in particular received a surprising challenge, with the near-simultaneous opening of a new Triennale exhibition in Milan highlighting many of the same nationalities and figures—Qatar and Saudi Arabia and Foster and even Ratti himself—served up in more digestible portions.

The Belgian Pavilion centered around plants. Photo © Luca Capuano, courtesy La Biennale di Venezia

There were signs of life, even glamour, around Venice during the vernissage—events by luxury outfits like Porsche, Cartier, and Milanese fashion brand La DoubleJ, more often the stuff of big commercial fairs—though behind it all there lurked a palpable sense of unease, one that only seemed exacerbated by the hectic psycho-visual environment at the Arsenale. Ratti reportedly accepted three quarters of the open-call applicants for participation in the main show; it was almost as though he were afraid to miss out on something, desperate to hop on any bandwagon that appeared bound for Tomorrowland. The most worrisome thought is that perhaps this was somehow correct: that in fact the combined intelligens of nature, culture, and technology are pointing us in a direction of complete social and intellectual incoherence. The future, as it appeared around the Grand Canal, might be an interesting place to visit. But it is not clear why anyone would want to live there.