A New Book Examines the Link Between Archigram’s Radical Vision and High-Tech London Architecture

This still-popular catchphrase, nailing the British preoccupation with World War II, comes from the 1975 sitcom Fawlty Towers. In a key episode, the eccentric manager of the titular crumbling hotel—played by ex-Monty Python member John Cleese—corrects himself with the slogan after tormenting bewildered German guests with references to the invasion of Poland. Still used self-deprecatingly in the United Kingdom to acknowledge their fixation on the war, the phrase also evokes ensuing self-esteem issues and conflicts behind the polished exterior of British society.

Architectures of the Technopolis: Archigram and the British High Tech, by Annette Fierro, Lund Humphries Publishers, 224 pages, $99.99.

Annette Fierro’s Architectures of the Technopolis explores the often manic impulses of postwar Britain, as expressed in its capital’s built fabric. The book is ostensibly an investigation into the origins of High Tech, the architectural movement that emerged from the UK in the late 20th century, and the role played by the Archigram-dominated British avant-garde of the 1960s. But the University of Pennsylvania associate professor has in fact written a dérive through contemporary London, in which the city is a text, ripe for analyzing. Her acute architectural analysis is melded with more subjective parsing of the libidinal urges that govern London’s development.

Fierro eschews a linear chronology, dividing the book thematically into sections on utopias, engineering, theater, infrastructure, and, finally, the memory of war. Knitting it together, just, is a central narrative about how Archigram and others, like the maverick architect and teacher Cedric Price, influenced the buildings and plans of the High Tech designers, a group that includes Richard Rogers, Norman Foster, and Michael Hopkins. Amid her descriptions of their impact on London, Fierro also throws in the Irish Republican Army, improv theater, Prince Charles, whatever and whoever as the opportunity arises. The effect mimics the sporadic and haphazard way London expands as much as it offers analysis of that development.

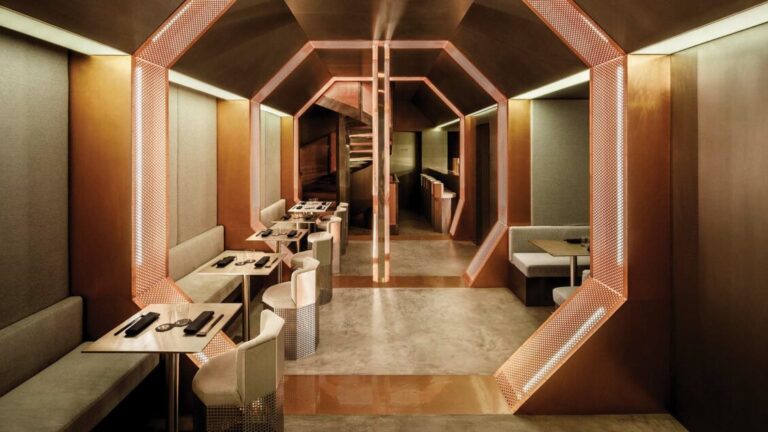

Detail from inside the Lloyd’s building, in London, completed in 1986 by Richard Rogers with Ove Arup. Photo © Annette Fierro, click to enlarge.

Fortunately, Fierro’s grasp of the historical linkage between early utopian thinking and the built work is very good. For example, she makes an excellent argument that the multilayered pedestrian routeways around the South Bank are influenced by Archigram’s Come-Go Project, an overlay of new transport modes on an existing city. She also rightly asserts the Olympics site in East London as the culmination of the architectural sensibility she’s tracking. However, she sometimes misses a beat when straying beyond architecture. Yes, the South Bank has a history of being “seamy.” It’s also the home to the Globe Theatre and a locale of other institutions of high culture. Her reading of Lord Rogers’s planning work as beyond reproach fails to address how it contributed to the UK’s disastrous housing shortages.

This, though, is the nature of a dérive. The line-by-line reading may now and again be awry, but the approach, which captures hard-to-quantify but real social forces, is compelling and useful. Where the strategy falls short is in seeing High Tech as a particular expression of London. The movement wasn’t an outcome of city conditions but rather the result of a global power’s being in the throes of huge change that happened to play out in its capital. Archigram and Price, the prime movers in her narrative, emerged from a troubled industrial heartland and an era of big military machinery. Influenced by the expanding consumer economy in the United States, they were among the first thinkers in the UK to consider the implications of impending deindustrialization and the emerging leisure class.

The machine was not an arbitrarily chosen aesthetic or some Lacanian system of image production to them. It was a literal site of class contest and, importantly, progress. Archigram imagined how industry might literally work for people: those who historically lived alongside—and were being replaced by—technology. Price, on the other hand, sought to offer industrial functions to the public for their amusement. One suspects it wasn’t a local authority funding issue that led to the cancellation of the Fun Palace, as Fierro suggests, but the fact that Price and his client, the theatrical impresario Joan Littlewood, believed that part of their Fun offer was giving the public enormous cranes to play with.

This lack of the class dimension in Architectures of the Technopolis is an odd omission, given the daft hierarchies of British society. It explains, though, Fierro’s seeming hesitation with her thesis: that High Tech—a static, monumental expression of the avant-garde work that precedes it—contains an element of sublimated violence emanating from World War II. Were she to appreciate the war and its aftermath as a lingering moment of cross-class social cohesion as well as destruction—as something to return to even when they know they shouldn’t—she might have made her conclusions about High Tech’s guilty secret regarding the war’s relevance more emphatic.

Still, Fierro’s book is an important addition to the scholarship on Archigram and High Tech. She has a fine appreciation of how technology is represented in Archigram’s work as well as its rhetorical power in High Tech architecture. However, she misses something important in overlooking machines as something that the British fought over, and then fought with, together—products of a shared, albeit contested, economic past. It’s a reality that emerged from Britain’s industrial hinterland and was revived by the war—that which shall not be mentioned but, invariably, is.