The Shepherd, designed by PRO; landscape by OSD; and OMA’s LANTERN open in Detroit

Detroit has seen plenty of development around its city center in recent years as many long-abandoned ruin-porn centerfolds have returned to use. The lights are back on even in Michigan Central Station, which is reopening this month. But it’s often still the same sad portrait of urban devastation elsewhere in the city. Nearly 30 percent of Detroit is abandoned; there were 18 permits for single-family houses issued in the city in 2023 (and only eight the previous year).

Little Village is part of an ongoing revival. The new mixed-use development calls Detroit’s East Village home, just a few blocks away from the landmarked Indian Village containing structures by Albert Kahn, Wirt Rowland, and Louis Kamper—but it’s also very near to all-but-vacant blocks.

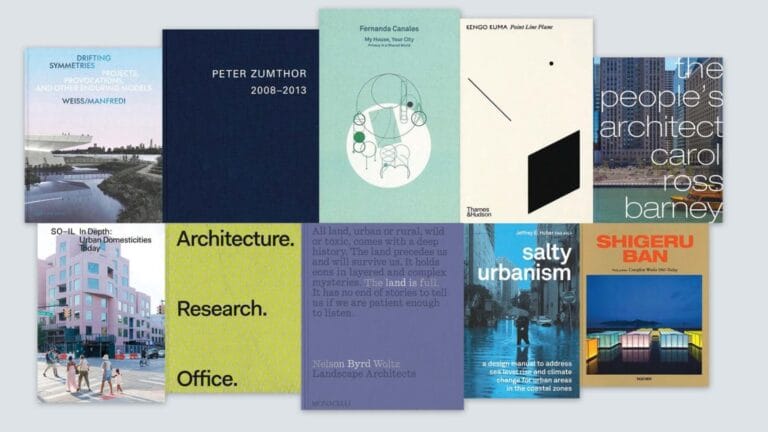

Little Village was developed by Anthony Curis and his wife, JJ—no strangers to development in East Detroit. Their newest project is scattered over a few blocks with a sort of town square core. The overall scope consists almost entirely of renovations. Elements include the church’s former rectory, well-renovated by Detroit-based ROSETTI into a B and B; a BIPOC-focused residency spaces for McArthur Binion’s foundation; two former homes renovated into commercial culinary spaces by Ishtiaq Rafiuddin of Undecorated; and numerous homes for artist live–work spaces (with even more to come). Two larger projects stand out: Anchoring the new scene are Peterson Rich Office’s (PRO) The Shepherd, a revamp of a church, and OMA’s LANTERN, which updates an old bakery.

Library Street Collective at The Shepherd

The principal draw for the undertaking in the first place was the 1912 Church of the Annunciation by Donaldson and Meier (the same firm that designed the Donald Stott building and the first Penobscot building downtown, among many others at the time). It’s a handsome Romanesque church that remained in partial use until 2016.

The parish was last called The Good Shepherd, a title that lives on in the building’s new name, The Shepherd. PRO handled this renovation, designed to produce a gallery and performance space for Library Street Collective. The challenge—and opportunity—was a distinguished church interior with stained-glass windows that were too beautiful to obscure but useless for hanging art.

The firm considered freestanding walls or dropped lighting grids, but abandoned both to instead settle on a scheme of two gallery cubes, one astride the nave and another nestled in the transept. These are steel-framed, plaster-fronted volumes bisected by entrances running along the church’s original terrazzo paths.

PRO principal Miriam Peterson explained, “As we developed the rooms themselves, we asked, how do we make them feel permanent rather than temporary? This is not a pop-up.” The solution was subtle detailing; reentrant corners and shadow gaps echo existing column details within the church, and brown metal tops echo cornice lines. The volumes provide flat walls for art, and each individual cube enables warm and even interior lighting in contrast to cooler uplighting elsewhere in the space.

The gallery interiors also curve to the ceiling, and Nathan Rich explained, “you don’t see any edges within that space.” PRO’s effort to “dematerialize” the walls reaches its fullest expression in one of these cubes as the materials literally do disappear in the form of an oculus, providing a vertical vista to the original vault.

This cube is also topped with a second-level viewing platform, accessed by a new stairway. Peterson said this addition offers a “moment of living in the barrel vault in a way you wouldn’t otherwise be able to do.” Elsewhere in the church visitors can witness other intriguing reuses: Former confessionals hold the Little Village Arts Library, for example, curated by Asmaa Walton of Detroit’s Black Art Library.

The Shepherd’s inaugural exhibit, Time Is Now, features work by eminent Detroit artist, sculptor, and muralist Charles McGee. He has a more permanent place just outside as well. Three sculptures he conceived before his death in 2021 have been realized on the lawn.

A Whole New Landscape

The core of the development, covering much of a block, is knitted together via a landscape by OSD. Its principal, Simon David, explained his aim to “create an environment that flowed seamlessly into and from the neighborhood, offering an invitation to visitors and utilizing materials, plantings, and forms that felt fitting to the decay and regrowth found in nearby vacant lots.”

Ecclesiastical inspiration continues outside, with the logic of the landscaping derived from the church, featuring a figurative nave, side altars, and apsidal geometry—all planted with choice meadow grasses and perennials, as well as red twig dogwood, selected for its avid growth properties and bright red stems that are visible in winter.

Brick salvaged from the upper floor of a nunnery across the street (whose remnant will soon house another gallery) was used in paving throughout the landscape. David explained his inspiration for this reuse, evoking Alvar Aalto: “The paving of the courtyard recalls his Muuratsalo Experimental House in a patchwork quilt of textures and patterns.” Some bricks not used for paving were repurposed elsewhere for paths or crushed for the site’s meditation loop, which also incorporates recycled glass in shades resembling the church’s stained-glass windows. Benches are salvaged from local trees, many downed during storms.

OMA’s LANTERN

A few blocks north, there’s LANTERN Detroit, a former bakery renovated by OMA to provide studio space for the Progress Arts Studio Council. It’s now an organization for artists with developmental and other disabilities as well as Signal-Return, a small art studio space that offers workshops on traditional letterpress printing.

Jason Long, principal at OMA, explained that “obviously the building is not some kind of grand cathedral, but it was intriguing because it was the result of this cluster of expansions.” Portions of the structure, built in three phases, had collapsed; OMA didn’t argue with gravity in two of these cases. One street-facing portion whose roof had tumbled was converted into an entrance courtyard. Another interior where a floor had fallen in was retained as a double-height space, simply because it made a dramatic impression on a first visit.

The building was largely windowless, and while bread doesn’t really need light, people do. OMA focused on adding simple windows in protruding vitrines to provide additional sunlight and display spaces in some portions. A new sawtooth roof also provides plenty of daylight and a splash of character. “We liked the idea that it created a profile from the street so the whole complex would have one moment where it appeared exuberant,” Long told AN.

One large, all-CMU building was a dilemma. The designers contemplated adding windows but those might have simply required demolishing the whole thing. Long explained the turning point: “Rather than trying to make a window, we acted on the wall by just drilling into it.” Using a core drill of the sort often used to insert technical elements, their incisions have expressive effects: Small holes cover the facade and are filled with more than 1,300 casters, creating luminous portholes. The move ended up inspiring the complex’s name.

It’s easy to be cynical about ostensible “arts-oriented” developments, as we know they usually involve only the thinnest varnish of actual art. Little Village is the real thing, however, and deserves lavish praise on that ground alone. There’s also no need to merely praise good works; the project is a strong demonstration of the benefits that premium firms can bring to relatively modest projects, as evidenced by the sharp work completed this spring in Detroit.

Anthony Paletta is a writer living in Brooklyn.