Cecilia Vicuña’s Poetry in Space

Cecilia Vicuña’s practice of recollecting — in both senses of gathering and remembering — doubles as an act of care for that which time, loss, and neglect have obscured, though not entirely erased. At Lehmann Maupin, this process turns inward, extending her expansive practice of retrieval to fragments of her own artistic past. A series of new oil paintings recreate drawings Vicuña made in 1978 that are now lost or destroyed, surviving only in her memory and through a small number of photographs. These original drawings were created after Vicuña — then living in Bogotá, Colombia, following her self-exile after Pinochet’s coup — embarked on a two-month journey across the Amazon to Rio de Janeiro. Along the way, she encountered Indigenous and Afro-Brazilian communities who offered hospitality and shared sacred rituals. These experiences inspired her syncretic depictions of Orixás, or Yoruba deities that guide and protect, which incorporate dreamlike imagery drawn from vernacular songs, native flora, and fragments of personal memory.

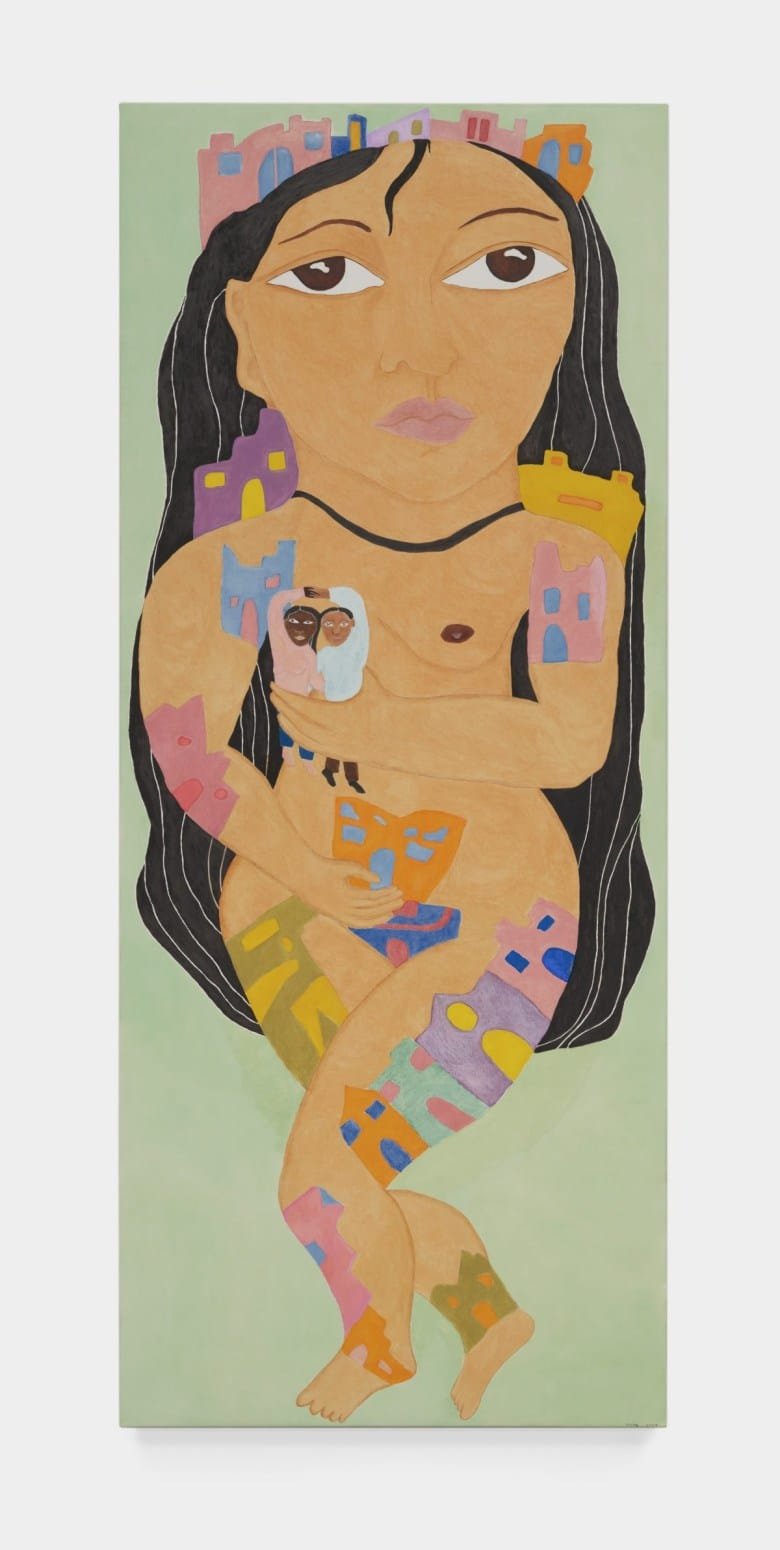

Created earlier this year, Vicuña’s paintings reanimate the imagery and memory of these lost hybrid divinities while expanding her pantheon with entirely new figures, each a repository of symbols rendered in bright pastels. “Santa Bárbara” (2024) is crowned with a cluster of houses, her form reimagined as a landscape of hills and steep slopes, lined with colorful neighborhoods like those Vicuña encountered in Northeast Brazil. In “La música latinoamericana” (2024), another portrait, Vicuña deifies Latin music, transforming instruments into anthropomorphic figures, their curves and shapes becoming extensions of the human body.

The exhibition also features the first United States presentation of Cecilia Vicuña’s monumental quipu, “NAUfraga” (2022), following its premiere at the 59th Venice Biennale. Once used as an Andean ancestral record-keeping device of knotted threads, the quipu is reimagined by Vicuña as an immersive “poem in space,” according to the press release, or a rhythmic cascade of shells, rocks, dried plants, and fragments of nets, jutes, and plastics gathered from the Venetian lagoon. For the first time, visitors can walk through “NAUfraga,” an experience akin to weaving through a shifting web of suspended sea wrack, where natural debris meets human-made refuse.

Left: Cecilia Vicuña, “Santa Bárbara” (2024), oil on canvas, 69 x 28 x 1 inches (175.3 x 71.1 x 2.5 cm); right: Cecilia Vicuña, “La música latinoamericana” (2024), oil on canvas, 69 x 28 x 1 inches (175.3 x 71.1 x 2.5 cm) (both © 2024 Cecilia Vicuña/Artist Rights Society (ARS), New York; photo by Daniel Kukla; courtesy the artist and Lehmann Maupin, New York, Seoul, and London)

With “A Prayer for the Rebirth of Peace in the All Lands” (2024), Vicuña continues her precarios (1966–) series, transforming natural and inorganic debris into small-scale, lyrical sculptures. Arranged across an expansive wall like relics of our throwaway culture, the sculptures are framed by a loosely scribbled chalk prayer about ecological precarity and political uncertainty: “We are at war with ourselves, with each other, and with the land.” The sculptures are delicately bound together in off-kilter forms that feel both precarious and playfully charismatic — among them, a metal coil tethered to a stone by a brittle twig, netting enveloping plastic and shell shards, and a withered sprig extending like an olive branch.

The work continues with a large piece of bark that rests on the floor, topped with smaller wooden fragments; visitors are invited to write single-word messages of peace, friendship, and respect in chalk across its surfaces. The clumsily layered languages — a prayer spoken across divides — analogize the tenuous yet vital struggle for peace in a contemporary moment riddled with global conflict. It suggests that, like these fragile assemblages, peace demands care, balance, and the resolve to hold together what might otherwise fall apart.

Beyond tending to that which disappears, Vicuña’s work is a reminder that what is lost or discarded — whether materials, histories, or traditions on the brink of vanishing — can be reimagined, underscoring that resilience often begins with recognizing value where others see waste.

Installation view of Cecilia Vicuña, “Prayer for the Rebirth of Peace in All Lands” (2024) (photo Clara Maria Apostolatos/Hyperallergic)

Installation view of Cecilia Vicuña, “Prayer for the Rebirth of Peace in All Lands” (2024) (photo Clara Maria Apostolatos/Hyperallergic)

Installation view of Cecilia Vicuña, La Migranta Blue Nipple (both © 2024 Cecilia Vicuña/Artist Rights Society (ARS), New York; photo by Daniel Kukla; courtesy the artist and Lehmann Maupin, New York, Seoul, and London)

Installation view of “NAUfraga” (2022), mixed media, fishnets with 161 hanging objects (83 Precario objects, 40 dried plants/wood, 36 fishnets/yute sac pieces), 19 7/10 x 39 2/5 x 226 2/5 inches (6 x 12 x 69 m) (photo Clara Maria Apostolatos/Hyperallergic)

Cecilia Vicuña: La Migranta Blue Nipple continues at Lehmann Maupin (501 West 24th Street, Chelsea, Manhattan) through January 11, 2025. The exhibition was organized by the gallery.

🔗 Source: Original Source

📅 Published on: 2024-12-15 23:03:00

🖋️ Author: Clara Maria Apostolatos – An expert in architectural innovation and design trends.

For more inspiring articles and insights, explore our Art Article Archive.

Note: This article was reviewed and edited by the archot editorial team to ensure accuracy and quality.